Strengthening social movements for inclusive water governance in Bangladesh

For generations, the people of Bangladesh’ flood-prone deltas have shaped their natural environment to support agricultural production. They used temporary embankments to keep tidal waters out of the floodplains for most of the year and let the rivers flow freely during monsoon season, allowing the sediment to settle on the floodplains as an important part of the delta formation process.

In the 1960s, permanent dikes were constructed along the country’s entire coast, disrupting the tidal ecosystem. The riverbed of many rivers completely silted up, while the land inside the polders gradually sunk below the riverbeds due to a lack of sedimentation. As a result, monsoon (rain) water became trapped within the polders, leading to severe waterlogging affecting the lives and livelihoods of over 2 million people throughout the southwest coastal zone during the last decades.

Massive grassroots resistance movements sprung up to demand change. One group even broke open a dike, resulting in a lawsuit for destroying government property. Local organisation and Both ENDS’ partner Uttaran stepped in to support the people’s quest for ecosystem restoration and social justice. Drawing from Uttaran’s experiences, programme development specialist Zahid Shashoto provides insights into the vital role NGOs can play in strengthening social movements.

Empowering people through institution building

The people demanded a return to indigenous tidal river management (TRM), but destroying the dikes themselves only created additional problems, including legal charges and increased distrust and miscommunication between formal water governance actors and past caretakers from the communities. Uttaran’s approach focuses on empowering people by strengthening their institutions. The NGO supports informal bottom-up movements to organise themselves into paani (water) committees and outline their demands in clear action plans. This levels the playing field and places the communities in a stronger position to negotiate their demands with the government. “We don’t want to act as a bridge between the community and the government”, Zahid emphasises. “There was something that people needed, that people were fighting for, and we started supporting them.”

Knowledge is key

According to Zahid, one of the most impactful roles of Uttaran and partner NGOs has been to exchange knowledge and information with the paani committees. Uttaran regularly organises meetings to inform communities about government policies and plans, while partner organisation CEGIS conducts environmental impact assessments to help people understand the potential impact of proposed water management interventions. Reports are summarised and translated into Bangla to make the information understandable and accessible, enabling community members to make informed decisions about their water resources. At the same time, the paani committees share knowledge and information obtained from their communities with Uttaran and CEGIS, for example problems related to the maintenance of infrastructure and the impacts of floods.

Inclusive and participatory decision-making

Waterlogging can be resolved by selectively opening dikes and closing them again after several years when natural sedimentation has raised the land level inside the polder and improved the navigability of the river – a technique similar to the Dutch “wisselpolders” which have been gaining attention in recent years. However, it is crucial to take into account the needs of local residents. Adequate compensation and alternative livelihood options should be provided to prevent conflicts and ensure social justice. Uttaran strengthens the capacities of paani committees to facilitate inclusive and participatory processes to understand local realities and engage community members in designing socially acceptable solutions. Paani committee members travel to villages along their river catchment to organise a mix of public gatherings and private meetings for specific socio-economic groups, such as women or youth. The process enables paani committees to formulate People’s Plans of Action that address community needs and ensure no group is left behind.

Vertical structures for effective advocacy

Finally, Zahid emphasises the importance of building vertical structures. Uttaran has helped create a network of paani committees at different levels, from small committees at the village level, larger committees at the wetland and river basin levels, to a central paani committee at the regional level. The expansive network has strengthened the communities’ collective voice in advocating for their demands at higher levels of government.

Through the tireless efforts of the paani committees, Uttaran and partner organisations, waterlogging has been resolved in the Kapotakkho river basin – a testament to the power of community-driven change. This case demonstrates the potential for civil society organisations to strengthen social movements and shape a more sustainable, equitable and democratic water governance model for Bangladesh and beyond.

Read more about this subject

-

Blog / 2 February 2019

Blog / 2 February 2019“Poldering” to face climate change

Last week Mark Rutte met with Ban Ki Moon, Bill Gates and World Bank Director Kristalina Georgieva in Davos. They are the chairpersons of the Global Commission on Adaptation, which was also founded by the Netherlands. This is an important organisation because, as Rutte wrote on Twitter, "climate change is the biggest challenge of this century," and as an international community we should "pay attention to the problems of the countries that are being threatened by climate change."

-

News / 13 August 2021

News / 13 August 2021Food sovereignty in the polders of Southwest Bangladesh

The situation in the southwest delta of Bangladesh is critical. Because of sea level rise, floods are increasing and the area is about to become uninhabitable, despite Dutch-style dikes and polders built in the previous century. Partner organisation Uttaran works with local communities on climate-friendly solutions that restore the living environment and give the inhabitants a say about their future and food production.

-

News / 22 March 2021

News / 22 March 2021The importance of a gender perspective in Dutch water policies

An increasing number of stakeholders in the Dutch water sector are acknowledging the importance of an inclusive approach to climate adaptation. However, where our knowledge institutes and companies are involved in delta plans and master plans, as in Bangladesh and the Philippines, this approach is proving difficult to apply in practice. Taking local realities, vulnerabilities and inequalities – such as those between men and women – as a starting point is essential for good plans that give everyone the opportunity to adapt to climate change.

-

External link / 19 June 2020

External link / 19 June 2020Community-based governance for free-flowing tidal rivers (Annual Report 2019)

Tidal River Management (TRM) is based on age-old community practices. In 2019, Uttaran helped ensure that TRM was seen by policymakers as a solution to waterlogging in the delta of Bangladesh, and that the voices of women and youth were being taken into account.

-

News / 4 July 2019

News / 4 July 2019Bangladesh: Involving communities for free rivers

Tidal rivers in the southwest coastal area of Bangladesh have been dying since flood plains were replaced by Dutch-style polders in the 70s. Rivers are silted up, and during monsoon season water gets trapped within embankments. Every year, this situation of waterlogging inflicts adverse consequences particularly on women, as they take care of the household in waterlogged conditions in the absence of men who travel to the city in search of temporary work. NGO Uttaran is advocating for a change in policy and practice.

-

Transformative Practice /

Transformative Practice /A Negotiated Approach for Inclusive Water Governance

A Negotiated Approach envisages the meaningful and long-term participation of communities in all aspects of managing the water and other natural resources on which their lives depend. It seeks to achieve healthy ecosystems and equitable sharing of benefits among all stakeholders within a river basin. This inclusive way of working is an essential precondition for the Transformative Practices that are promoted by Both ENDS and partners.

-

News / 13 October 2023

News / 13 October 2023Water is life, water is food: World Food Day 2023

"Water is life, water is food" is this year's theme for World Food Day. Our partners around the world know all too well that this is a very true sentence. To celebrate World Food Day 2023 this October 16th, we'd like to show a few examples of how our partners fight for the right to water and this way, contribute to local food sovereignty at the same time.

-

News / 22 January 2024

News / 22 January 2024Is the Netherlands’ reputation as a world leader in the field of water knowledge deserved?

The Netherlands is a major player in the global water sector, but our investments can quite often lead to human rights violations and environmental problems in the countries where they are made. What can a new Dutch government do to reduce the Netherlands’ footprint beyond our borders? Ellen Mangnus spoke to various experts about this issue: today, part 3.

-

News / 14 June 2021

News / 14 June 2021Concerns about a new airport in vulnerable Manila Bay

In Manila Bay, a vulnerable coastal area next to the Philippine capital city, a new airport is being planned, with involvement of the Dutch water sector. Local civil society organisations raised their concerns about this airport, which has large impact on the lives of local residents and on the ecosystem.

-

News / 14 December 2023

News / 14 December 2023The Netherlands can radically reduce its agrarian footprint

In the weeks following the elections, Both ENDS is looking at how Dutch foreign policy can be influenced in the coming years to reduce our footprint abroad and to work in the interests of people and planet. We will be doing that in four double interviews, each with an in-house expert and someone from outside the organisation.

-

Event / 23 March 2023, 13:15 - 14:30

Event / 23 March 2023, 13:15 - 14:30Making finance for gender just water and climate solutions a reality!

The UN Water Conference is an important event that brings together stakeholders from around the world to discuss water and climate solutions. This year, GAGGA is organizing a side event during the conference that you won't want to miss!

On Thursday March 23rd, from 1.15 -2.30 pm, GAGGA will present their commitment to support, finance, and promote locally rooted, gender just climate and water solutions within the Water Action Agenda. This event will inspire other stakeholders to join in their commitment, while presenting inspiring examples of such solutions presented by local women from Nepal, Kenya, Paraguay, Mexico, and Nigeria.

-

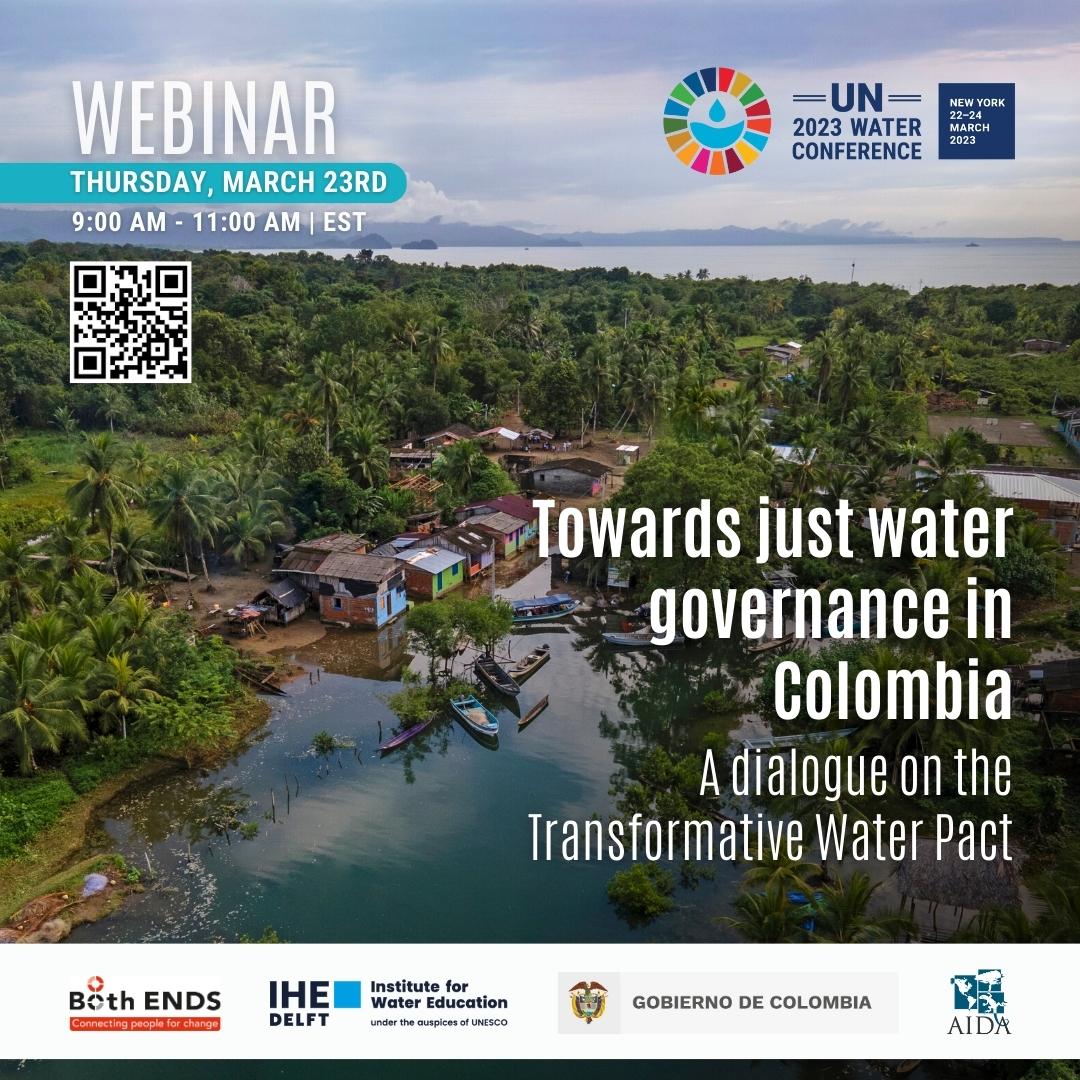

Event / 23 March 2023, 09:00 - 11:00

Event / 23 March 2023, 09:00 - 11:00Towards just water governance in Colombia; a dialogue on the Transformative Water Pact

Online side event at the UN Water conference in New York

This event will present The Transformative Water Pact (TWP), an innovative framework for water governance that has been developed by environmental justice experts from around the world. The TWP will serve as a starting point for dialogue between representatives of the government of Colombia, academia, regional and international NGOs in relation to Colombia's current ambitions in multi-scalar water governance.

-

Press release / 20 March 2023

Press release / 20 March 2023A Transformative Water Pact : A radical response to the global water governance crisis

Academics and civil society representatives from around the world came together to articulate an alternative vision and framework for water governance, in the run-up to the UN Water Conference 2023 in New York. The Transformative Water Pact was developed in response to the continued exploitation of nature, neglect of human rights and the extreme power-imbalances that characterize contemporary water governance throughout the world. It details an alternative vision of water governance based on the tenets of environmental justice, equality and care.

-

Publication / 15 March 2023

-

News / 23 March 2020

News / 23 March 2020Women in Latin America claim their right to water

In many places in Latin America, access to clean water is under great pressure from overuse and pollution, often caused by large-scale agriculture or mining. This has significant impact, especially on women. In March, with International Women's Day on March 8 and World Water Day on March 22, they make themselves heard and claim their right to water.

-

News / 16 August 2016

News / 16 August 2016Art as a powerful messenger: music from the Pantanal

10 songs: that is the result of a 4 day long, 450 km boat trip through the Pantanal with 36 people. The project Pantanal Poética sought and found a new way to look at the Pantanal, a valuable but threatened nature reserve on the border of Brazil, Bolivia and Paraguay.

-

Publication / 1 July 2016

-

News / 22 March 2012

News / 22 March 2012What did Both ENDS do at the World Water Forum?

Halls filled with booths, stands, professionally set up corners, wifi-spots. Big rooms where lectures, interactive sessions and workshops are held. People from all corners of the world and from different kinds of sectors (companies, government, and social organisations) are gathering here for five days. They have one thing in common: they are talking about water. The sixth World Water Forum in Marseille is about 'solutions'. For water issues, that is. Almost a billion people worldwide have to cope without clean drinking water.

-

Publication / 21 March 2023

-

News / 21 March 2023

News / 21 March 2023Agua es vida: Both ENDS and water governance

Water is literally life, the lifeblood of ecosystems, of nature, of humans. However, in many places the distribution and use of water is unjust and unsustainable. Water management is generally focused on short-term economic interests, on maximizing the profit of a well-connected few at the expense of people and nature. This dominant view of water and water management has its origins in the European industrial revolution, which became the global norm through colonialism and globalization. But according to Melvin van der Veen and Murtah Shannon, water experts at Both ENDS, this view will have to give way to equitable, sustainable and inclusive water management. Both ENDS cooperates with and supports communities and organisations worldwide who are working to this end.